# Adding Functions to the Calculator

# Añadiendo funciones a la calculadora

Queremos extender nuestra calculadora para que soporte funciones con una sintáxis como la de este ejemplo:

x = 10, # This x is global

f = fun (a) {

x = a+2i, # This x is local

3i*x # returned value

},

b = f(4),

print(b), # -6+12i

print(x) # 10

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Vamos a hacerlo teniendo en cuenta las siguientes consideraciones:

- Limitaremos las funciones a que reciban 0 o 1 parámetros

- El cuerpo de la función es una expresión entre llaves

{ e } - Las funciones retornan el valor evaluado para

e. - Las funciones crean un nuevo ámbito: tanto los parámetros como las variables iniciadas dentro de la expresión de una función serán locales a la función

- Tan pronto una variable es inicializada dentro del cuerpo de una función se la considera declarada y es local a la función (parecido a como se hace en Ruby)

- Nuestras funciones son anónimas

Cuando se llame a nuestro transpiler con la entrada anterior, se debe generar un programa JS equivalente a este:

✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-scop2.calc

#!/usr/bin/env node

const Complex = require("/Users/casianorodriguezleon/campus-virtual/2223/pl2223/practicas/functions/functions-solution/src/complex.js");

const print = x => { console.log(x); return x; };

let $x, $f, $b;

(

(

(

$x = Complex("10"),

$f = function($a) {

let $x;

return $x = $a.add(Complex("2i")),

Complex("3i").mul($x);

}

),

$b = $f(Complex("4"))

),

print($b)

),

print($x);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Ámbitos

Observe como declaramos como globales $x, $f y $b pero la función tiene como locales

el binding del parámetro $ay el binding de la variable $x que oculta al nombre $x global.

# Las funciones son expresiones

# Funciones que retornan funciones

Las funciones que introduzca podrán recibir como argumento una función y también pueden retornar funciones. En el siguiente ejemplo sum es una función que retorna una función:

sum = fun (n) {

fun(x) { n+x }

},

r = sum(4)(5),

print(r) # 9

2

3

4

5

cuya traducción podría ser:

➜ functions-solution git:(functions) ✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun3.calc

#!/usr/bin/env node

const Complex = require("/Users/casianorodriguezleon/campus-virtual/2223/pl2223/practicas/functions/functions-solution/src/complex.js");

const print = x => { console.log(x); return x; };

let $sum, $r;

(

$sum = function($n) {

return function($x) {

return $n.add($x);

};

},

$r = $sum(Complex("4"))(Complex("5"))

),

print($r);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

# Funciones que reciben funciones y retornan funciones

En este otro ejemplo, la función add recibe una función f y retorna otra función que a su vez espera como argumento otra función g la cual retorna una función que es la función que suma a su argumento x los valores de la primera f(x) y la segunda g(x):

add = fun(f) {

fun(g) {

fun(x) {

f(x)+g(x)

}

}

},

square = fun(x) { x*x },

double = fun(x) { 2*x },

print(add(square)(double)(4)) # 24+0i

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Cuando la compilamos

✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun4.calc

#!/usr/bin/env node

const Complex = require("/Users/casianorodriguezleon/campus-virtual/2223/pl2223/practicas/functions/functions-solution/src/complex.js");

const print = x => { console.log(x); return x; };

let $add, $square, $double;

(

(

$add = function($f) {

return function($g) {

return function($x) {

return $f($x).add($g($x));

};

};

},

$square = function($x) {

return $x.mul($x);

}

),

$double = function($x) {

return Complex("2").mul($x);

}

),

print($add($square)($double)(Complex("4")));

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

y cuando la ejecutamos obtenemos:

✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun4.calc | node -

{ re: 24, im: 0 }

2

# Encadenamiento de llamadas

Encadenamiento de llamadas

Estos dos ejemplos ilustran que puesto que las funciones retornan funciones es por lo que se solicita soportar una sintáxis que permita llamadas encadenadas del tipo f(a)(b)()(c)()

# Comentarios con "#"

Como se ve en los ejemplos anteriores se deberán admitir comentarios de una línea que van desde la aparición del carácter # hasta el final de la línea

# Operadores Lógicos y de Comparación

Añada operadores lógicos

&¶ elandlógico,||para elorlógico y- el prefijo

!para elnot - además de los valores

trueyfalse

# Short Circuit Evaluation and if then else

La interpretación de estos operadores se hará como en JavaScript:

valores distintos de cero en un contexto lógico se evaluan a true, etc.

Además las evaluaciones se harán en circuito corto (short-circuit) de manera que el siguiente programa calcula el factorial de un número natural:

fact = fun(n) {

!(n == 0) && n * fact(n - 1) || 1

},

print(fact(5))

2

3

4

Short Circuit and if then else

Nótese que:

b && cimplicaif (b) then cb || cimplicaif (!b) then cb && c || dimplicaif b then (if c then ; else d) else d

Que cuando se compile dará:

✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-recursive2.calc

#!/usr/bin/env node

const Complex = require("/Users/casianorodriguezleon/campus-virtual/2223/pl2223/practicas/functions/functions-solution/src/complex.js");

const print = x => { console.log(x); return x; };

let $fact;

$fact = function($n) {

return !$n.equals(Complex("0"))

&& $n.mul($fact($n.sub(Complex("1"))))

|| Complex("1");

},

print($fact(Complex("5")));

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

y cuando se ejecute dará:

✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-recursive2.calc | node -

{ re: 120, im: 0 }

2

# Type Handling in Dynamic Languages

Type checking is the process of verifying and enforcing constraints of types in values. The language type-checker determines whether these values are used appropriately or not.

On the complexity of type checking

In non-typed languages such as the one we are using here, the complexity in handling types moves from the compilation phase to the execution/interpretation phase.

Now our language has several types:

- Complex numbers,

- Functions of various types:

- functions without arguments that return a complex,

() → (Complex) - functions with complex argument that return a function

(Complex) → (* → *), - functions that return logical values,

(*) → (Boolean), etc.

- functions without arguments that return a complex,

- Booleans

Questions

- What to do if the booleans are subjected to arithmetic operations?

- What if the same is done with functions?

- What if you add a number with a function?

For each operation, there are numerous possible type combinations and decisions need to be made about them.

In either case, a guidance error message should be issued for any operation that is decided not to be supported.

# Type Checking: Basic concepts

For an introduction to the basic concepts on type checking see the section Type Checking: Basic Concepts

# Function Arithmetic

For example, we might decide to generalize to support arithmetic operations on functions whenever they make sense, so that a program like this:

f = fun(x) { 2*x },

g = fun(x) { 3*x },

r = fun(y) { 3*y },

h = g + f,

k = g * f,

e = g == r,

print(h(1+i)), # 5 + 5i

print(k(2-i)), # 18 - 24i

print(e(1)) # true

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

will work resulting in an execution like this:

➜ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-add.calc | do not give -

{ re: 5, im: 5 }

{ re: 18, im: -24 }

true

2

3

4

# Arithmetic of Functions ad numbers

But we may also want to allow functions to be operated on numbers (by extending a number as the function constant on that number):

f = fun(x) { 2*x },

h = f + 3, # 3 is the constant function f(x) = 3 for all x

print(h(1+i)) # 5 + 2i

2

3

which would be interpreted as:

✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-add1.calc | do not give -

{ re: 5, im: 2 }

2

# Arithmetic of Functions and Booleans

It would also be possible to extend addition/subtraction etc. to a function with a boolean.

One possible interpretation would be to promote the boolean value true to 1+0i and false to 0:

f = fun(x) { 2*x },

h = f + true,

print(h(1+i)) # 3 + 2i

2

3

which when executed could give:

✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-add2.calc | do not give -

{ re: 3, im: 2 }

2

# New Semantic needs New Syntax

Rethink your Syntax

Another fact of interest is that the extension of the operations can lead to rethinking the syntax. For example, why not extend the call syntax to allow calls of the form (f+g*h)(x)(y)?

For example, given the login program:

f = fun(x) { x+1 },

g = fun(x) { x+2 },

print((f+g)(3)) # 9

2

3

This would be the expected behavior:

➜ functions-solution git:(extendedcalls) ✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-call.calc

#!/usr/bin/env node

const Complex = require("/Users/casianorodriguezleon/campus-virtual/2223/pl2223/practicas/functions/functions-solution/src/complex.js");

const print = x => { console.log(x); return x; };

let $f, $g;

(

$f = function($x) {

return $x.add(Complex("1"));

},

$g = function($x) {

return $x.add(Complex("2"));

}

),

print(

$f.add($g)(Complex("3"))

);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Which when executed gives rise to:

➜ functions-solution git:(extendedcalls) ✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-call.calc | do not give

-

{ re: 9, im: 0 }

2

3

# Type Promotion

Promoting types

A strategy that can help if you choose to extend the behaviors of our types is to establish a line of promotion/extension from the simplest to the most complex types:

- a boolean when operated with a number can be seen as a number, (

falseis coerced to0andtrueto1) - a number when operated with a function can be seen as a constant function, (

3is coerced tox => 3)

So, for instance,

- if

fis a function→ then (true + f)(x) = (1 + f)(x) = 1 + f(x) - if

fis a function→ ( → ) then (true +f)(x)(y) = (1+f)(x)(y) = (1 + f(x))(y) = 1 + f(x)(y)

For instance, considere the following example:

f = fun(x) { fun(y) { x+y} },

print((f+2)(3)(5)) # 10

2

When compiled we have to produce something like this translation:

➜ functions-solution git:(functions) ✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-call2.calc

#!/usr/bin/env node

const Complex = require("/Users/casianorodriguezleon/campus-virtual/2223/pl2223/practicas/functions/functions-solution/src/complex.js");

const print = x => { console.log(x); return x; };

let $f;

$f = function($x) {

return function($y) {

return $x.add($y);

};

},

print(

$f.add(Complex("2"))(Complex("3"))(Complex("5"))

);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Notice how the function $f has now a method add that is called with argument Complex(2). The run time library support is inserting this new behavior to the funcion $f.

it can be considered an example of Duck Typing.

Duck Typing

Duck typing is usual in dynamically typed languages: the set of methods and properties of the object determine the validity of its use. That is: two objects belong to the same duck-type if they implement/support the same interface regardless of whether or not they have a relationship in the inheritance hierarchy.

The term refers to the so-called duck test: If it waddles like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it's a duck!

this way, via the run time support injecting behavior as .add to the functions objects we can make the JS interpreter to produce this output:

➜ functions-solution git:(functions) ✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-call2.calc | node -

{ re: 10, im: 0 }

➜ functions-solution git:(functions) ✗

2

3

# Language Symmetry

Symmetry

If such a decision is chosen, it is convenient to maintain symmetry.

That is, that someFunction + someNumber

provide the same value as someNumber + someFunction.

This implies that if we add the add method to the Functions so that it takes a complex number as an argument

SomeFunction.add(someComplexNumber) should also be extended to add for complex numbers to support functions as arguments

someCompleNumber.add(SomeFunction).

That is, if we consider the symmetric of the former example with 2+f instead of f+2 it has to work the same way:

➜ functions-solution git:(extendedcalls) ✗ cat test/data/input/test-fun-call2-symmetric.calc

f = fun(x) { fun(y) { x+y} },

print((2+f)(3)(5)) # 10

2

3

The translation produces a memberExpression Complex("2").add($f):

➜ functions-solution git:(extendedcalls) ✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-call2-symmetric.calc

#!/usr/bin/env node

const Complex = require("/Users/casianorodriguezleon/campus-virtual/2223/pl2223/practicas/functions/functions-solution/src/complex.js");

const print = x => { console.log(x); return x; };

let $f;

$f = function($x) {

return function($y) {

return $x.add($y);

};

}, print(Complex("2").add($f)(Complex("3"))(Complex("5")));

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

If we extend the behavior of Complex appropriately it can work:

➜ functions-solution git:(extendedcalls) ✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-fun-call2-symmetric.calc | node -

{ re: 10, im: 0 }

2

# Be bold in your designs but keep them simple.

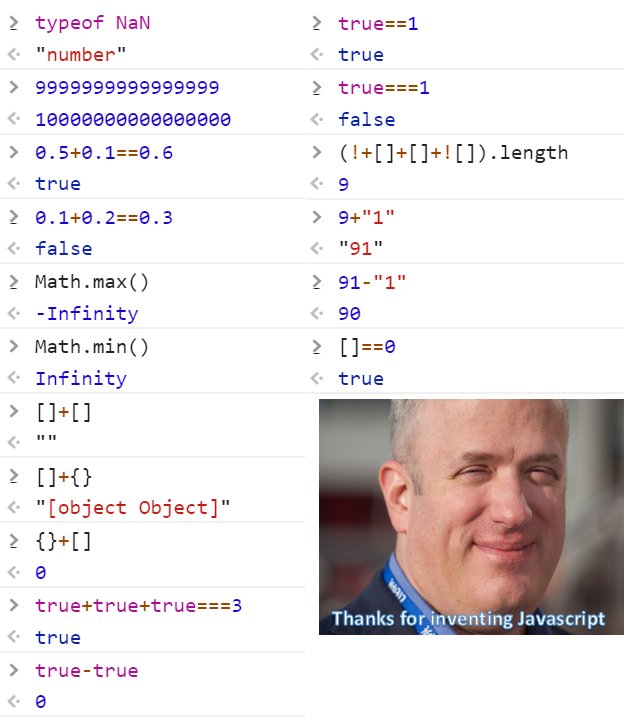

Allowing too much freedom and inconsistent decisions may produce surprising results. JS is quite famous for this:

Simplify and do not extend

An alternative option is to block most extensions and produce appropriate error messages for disallowed operations. Another not so radical would be to allow some operations to fail and others not.

For example, we could decide that two logical values can be checked for equal but cannot be added, so this program:

b = false == false,

print(b), #true

c = true + true # error

2

3

would result in output like this:

✗ bin/calc2js.mjs test/data/input/test-logic2.calc | do not give -

true

Error. Unsupported operator "+" for type boolean

2

3

In this lab, the decision to adopt on the combinations of operations and types is left to your discretion, such as: Do we admit adding a function and a Boolean and produce a result or, on the contrary, do we consider it an error? Certain extensions could be the subject for the final TFA.

In any case, remember that you must ensure that the error messages issued must be as explanatory as possible.

# Smells, The Open Closed Principle, the Switch Smell and the Strategy pattern

See section The Open Closed Principle and the Strategy Pattern

# Pruebas, Covering e Integración Continua

Escriba las pruebas, haga un estudio de cubrimiento usando c8 (opens new window) y añada integración continua usando GitHub Actions.

Lea las secciones Testing with Mocha y Jest.

# Documentación

Documente

el módulo incorporando un README.md y la documentación de la función exportada usando JsDoc.

Lea la sección Documenting the JavaScript Sources

# References

- COMP442/6421 - Compiler Design - week 8 - AST traversal using the Visitor pattern. Concordia University, Montreal , Canada. 2022

- Compiler Design Module 34 : Semantic Analysis Introduction to Scope. IITI Delhi. Compiler AI Labs. 2020

- Compiler Design Module 35 : Semantic Analysis as Recursive Descent over AST. IITI Delhi. Compiler AI Labs. 2020

- ast-types: See the scope section

- recast